Enjoy more cartoons like these

Enjoy more cartoons like theseXKCD updates every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

Thank you for bringing up the illuminating distinction between equality feminism (women treated the same as men) and difference feminism (specific role differences require specific protection for women to allow them to participate equally).What is biology and what is learned gender role in the perceived differences between men and women? Because I have 5 very different brothers and 4 very different daughters, I question overemphasis on innate differences. The spread of differences among people of the same sex seem as great or greater as the differences between the sexes. At 8 months, my grandson clearly resembles his adventurous, world-traveling mother; he is as different from two of his aunts as his mother is. We would need several generations of both men and women equally involved in raising young children to make any significant judgment about innate sex differences.

Childbearing shifts the equation. Doctors advocate nursing for a year as the ultimate preventive health measure. So for about two years per child, women do need special accommodations. As you say, Europe in general has much better support for new mothers. They recognize that everyone benefits if new parents can afford to bond with their newborns and children receive as much parental care as possible in the early years. Fathers and mothers are equally capable of parenting young children; exclusive breastfeeding only last six months. Many heroic women now manage to work full time and give their infants only their own milk.

Day care of infants and toddlers, if done right, is usually prohibitively expensive financially. Babies usually get sick far more often in day care, and their parents have to scramble for alternatives just as their babies are needier and fussier. Premature group care is frequently emotionally expensive for infants and toddlers. My oldest brilliantly explained her daily meltdown after full-day kindergarten: "Mommy I used all my goodness up at school." Society needs to make changes so that both parents could work a part-time and/or home-based schedule in their children's earliest years without losing their benefits or harming their possibilities for career advancement. Onsite day care could be an alternative offered by all large enough companies and organizations.

Here are two central facts about American birth: first, the US spends more per capita than any other developed nation on maternity care. Second, the World Health Organization ranks the US thirtieth out of 33 developed countries in preventing maternal mortality, and 32nd in preventing neonatal mortality. Our country is not doing well by mothers and babies.

Both these books describe, in splendid detail, the myriad interventions of “active management”—the practices perpetrated upon even a healthy woman planning the most unremarkable of births. Although these practices may help in critical situations, they are more likely to cause harm than good in a normal birth. For example, active management includes the induction of labor in as many as forty percent of all American births, even though this leads to longer and more painful labors and “ups a woman’s chance of a [cesarean] section by two to three times,” according to Block. ...Active management also includes speeding up a woman’s labor with the use of Pitocin in perhaps a majority of American hospital births today. According to Block, “a recent American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG )survey found that in 43 percent of malpractice suits involving neurologically impaired babies, Pitocin was to blame.” And it includes routine electronic fetal monitoring, used in 93 percent of hospital births even though studies show that its only effect is to increase the c-section rate.The quintessential intervention is the cesarean section, which is how nearly thirty percent of American women delivered their babies last year. WHO says that when a population has a c-section rate of higher than fifteen percent, the risks to the mother and baby outweigh the benefits—and a WHO study found that “the main cause of maternal deaths in industrialized countries is complications from anesthesia and cesarean section,” Block reports. She cites another study published last year, of 100,000 births, which found that “the rate of ‘severe maternal morbidity and mortality’—infection requiring rehospitalization, hemorrhage, blood transfusion, hysterectomy, admission to intensive care, and death—rose in proportion to the rate of cesarean section.” As for the baby, other research has found that “preterm birth and infant death rose significantly when cesarean rates exceeded between 10 and 20 percent,” and that “low-risk babies born by cesarean were nearly three times more likely to die within the first month of life than those born vaginally.” Nonetheless, ACOG not only rejects the fifteen percent target, but even continues to support the idea of elective c-section.

What are your alternatives to an interventionist and/or C section birth?

As evidence is increasingly showing, the people who best enable normal births are midwives. Obstetricians, after all, are surgeons, and many never witness a natural, normal birth in their training. Midwives, in contrast, are women who know that one of the best answers to pain is sitting in a warm tub, who know how to manually palpate a woman’s belly to find the baby’s weight and position, and who know how to help a woman handle labor in ways that facilitate birth.But midwifery in the US is up against some powerful forces—mainly, again, obstetricians and American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Doctors throughout American history have worked to discredit midwives—labeling them dirty, uneducated, and unskilled—and to drive them out of business. Today certified nurse-midwives who practice in hospitals report having their hands tied by doctors and hospital protocol.

Is it possible for change to come from women themselves?

Block ends with a challenge to today’s organized feminists to bring birthing under the umbrella of “choice,” quoting childbirth educator Erica Lyon, who says, “I think this is the last leap for the feminist movement. This is the last issue for women in terms of actual ownership of our bodies. It will take a revolution."

These books deal only peripherally with one of the most problematic issues: what do you do when women freely choose, or think they freely choose, medical procedures that increase their risk and that of their children? If women believe their obstetricians are their best advocates, how do you convince them to think skeptically? Until women take birth into their own hands, until they realize that doctors are not necessarily women’s advocates, until they seek out the evidence, which is in these books but not in doctor’s offices, about the normalcy of birth and the dangers of interventions, they are going to continue to believe that birth is a crisis about which only one person – the obstetrician – knows best.

We fought this battle in the 1970s and early 1980s and thought we were winning. I had four children between 1973 to 1982; two were hospital births, two were home births. I employed one obstetrician, one family practioner, and two nurse-midwives. I was given pitocin against my will for my only OB-assisted birth; I received no other medications.

This is a picture of Robert Kennedy speaking at my graduation from Fordham University in 1967. RFK was running for president in 1968 when he was assassinated June 5, ten days before my wedding. I had a final wedding dress fitting the day of the assassination, and I was in tears the whole time.

This is a picture of Robert Kennedy speaking at my graduation from Fordham University in 1967. RFK was running for president in 1968 when he was assassinated June 5, ten days before my wedding. I had a final wedding dress fitting the day of the assassination, and I was in tears the whole time. No problem, riddle, or formula seems to be beyond his ken. He is the outstanding scientist of St. Francis College; he is the winner of the coveted Smith Memorial Medal for excellence in Science. Yet even his own brilliance could not fathom the enigma of Joe Koch. In many ways Joe is a walking paradox. He seldom laughs outright; in fact his picture would lead one to believe that he is a sombre pessimist. Yet it is his nimble wit that makes him a distinctive personality. His humor is never loud; rather it is whimsical and epigrammatic.

No problem, riddle, or formula seems to be beyond his ken. He is the outstanding scientist of St. Francis College; he is the winner of the coveted Smith Memorial Medal for excellence in Science. Yet even his own brilliance could not fathom the enigma of Joe Koch. In many ways Joe is a walking paradox. He seldom laughs outright; in fact his picture would lead one to believe that he is a sombre pessimist. Yet it is his nimble wit that makes him a distinctive personality. His humor is never loud; rather it is whimsical and epigrammatic. No problem, riddle, or formula seems to be beyond his ken. He is the outstanding scientist of St. Francis College; he is the winner of the coveted Smith Memorial Medal for excellence in Science. Yet even his own brilliance could not fathom the enigma of Joe Koch. In many ways Joe is a walking paradox. He seldom laughs outright; in fact his picture would lead one to believe that he is a sombre pessimist. Yet it is his nimble wit that makes him a distinctive personality. His humor is never loud; rather it is whimsical and epigrammatic.

No problem, riddle, or formula seems to be beyond his ken. He is the outstanding scientist of St. Francis College; he is the winner of the coveted Smith Memorial Medal for excellence in Science. Yet even his own brilliance could not fathom the enigma of Joe Koch. In many ways Joe is a walking paradox. He seldom laughs outright; in fact his picture would lead one to believe that he is a sombre pessimist. Yet it is his nimble wit that makes him a distinctive personality. His humor is never loud; rather it is whimsical and epigrammatic. I have always loved this picture of me and my brother Joe, 18 months younger, taken in the fall of 1948. This might have been the last time I had the advantage over Joe. I seem smugly satisfied by his captivity. In my baby book my mom claims that "Mary Jo and Joe were always ahead of mother. Often though she forgot he was so small and played rough." I am dubious; he does not look intimidated. Joe always pulled the wool over mom's eyes. She never knew that Joe's babysitting consisted of taking his brothers out on the roof and daring them to jump into the swimming pool.

I have always loved this picture of me and my brother Joe, 18 months younger, taken in the fall of 1948. This might have been the last time I had the advantage over Joe. I seem smugly satisfied by his captivity. In my baby book my mom claims that "Mary Jo and Joe were always ahead of mother. Often though she forgot he was so small and played rough." I am dubious; he does not look intimidated. Joe always pulled the wool over mom's eyes. She never knew that Joe's babysitting consisted of taking his brothers out on the roof and daring them to jump into the swimming pool. My mom and dad must have been dedicated to nurturing their children's unique gifts at whatever cost, so Santa was allowed to bring Joe a drum and me a baton. We lived in a tiny two bedroom, one bathroom, one-story house. Was Joe allowed to play the drum inside? This picture proves the falsity of Joe's accusation that I regularly beat him up. If I been a brother slayer, surely my mom and dad would not have trusted me with such an effective weapon. Richard obviously had not a fear in the world that my baton would come in contact with his head or his drum.

My mom and dad must have been dedicated to nurturing their children's unique gifts at whatever cost, so Santa was allowed to bring Joe a drum and me a baton. We lived in a tiny two bedroom, one bathroom, one-story house. Was Joe allowed to play the drum inside? This picture proves the falsity of Joe's accusation that I regularly beat him up. If I been a brother slayer, surely my mom and dad would not have trusted me with such an effective weapon. Richard obviously had not a fear in the world that my baton would come in contact with his head or his drum.

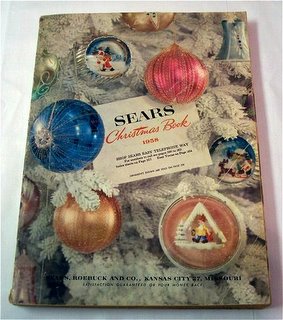

How did we know what we wanted for Christmas in the days before television, glossy newspaper and magazine advertisements? The Sears Christmas Wish Book was our bible. After it came in early November, my mom used to hide it for a few weeks, so we didn't have months to want things she couldn't afford to give us. I don't recall regular visits to department stores, though we probably did visit Santa Claus occasionally.

How did we know what we wanted for Christmas in the days before television, glossy newspaper and magazine advertisements? The Sears Christmas Wish Book was our bible. After it came in early November, my mom used to hide it for a few weeks, so we didn't have months to want things she couldn't afford to give us. I don't recall regular visits to department stores, though we probably did visit Santa Claus occasionally.