August 31, 2008

Feminists Don't Tell Palin How To Mother

I was sickened and infuriated by the misogynistic, sexist attacks on Hillary coming from the media and from the progressive blogs I regularly read. I found it necessary to stop reading and commenting on many blogs and retreat to feminist ones. For almost a year I have been writing posts on how Obama needs to campaign as a feminist.

I have been disappointed by Obama's and the DNC's continued reluctance to address misogyny and sexism. I prayed that Obama would make a speech on sexism equivalent to his speech on racism. I am not entirely sure he gets it.

I had very mixed feelings about Michelle Obama's superb speech. It disturbs me greatly that she felt compelled to downplay her educational and career achievements and stress being a daughter, sister, wife and mother. Michelle has had to quit her job and her mother retired early to help take care of the children. Obama hardly sees his children by his own admission.

The Democratic Convention left me optimistic that the Obama and Hillary supporters could unite and defeat McCain. I thought we might be spared sexist onslalughts for the rest of the campaign.

Then McCain appointed Palin, and I am drowning in sexist bilge from leftist blogs. She is not experienced enough to be vice president. But she is not a twit, a VPILF, a beauty queen, an abusive mother. Too many of the young progressive bloggers who attacked Clinton can't seem to help themselves; they require a woman to kick around.

The sexism is different this time. Much of it concentrates on her mothering. Details of her labor are analyzed, debated, criticized. Her daughter is potrayed as her sibling's mother. Pictures of her daughter's belly are scrutinized. People are comparing her marriage certificate with her first son's birth certificate. This is just creepy; it feels stalkerish. That Democrats are doing it is revolting.

People don't seem to be able to get beyond stereotyping conservative women to hear that her husband plans to be the primary parent. Abortion is not the only feminist issue. Mothers' being able to care for their children and hold demanding jobs, fathers' sharing parenting equally with mothers, seem even more important to me. Palin has laughingly dismissed people who questioned her ability to mother and to govern as neanderthals. It must do girls good to see that the mother of young children can also run for major office. Despite the fact that I would never vote for her in a 1000 years, I still got a kick out of a picture of Palin's signing a bill into law, wearing her baby in a sling.

As the mother of 4, I am offended by the jeering that she obviously doesn't know how babies are made. Have we decided we don't need the vote of anyone who dared to have more than two kids? Her right-wing nuttery is being exaggerated. She doesn't have a record of imposing her views on anyone. I find it very upsetting that OBs are now recommending that every women be screened for Down's Syndrome, and that most people chose to end their pregnancy if they have a DS baby. I admire her keeping the baby and not hiding him at home.

Of course, Obama has considerably more experience. But being the mother of 5 over a period of 20 years probably is more than the equivalent of being a community organizer.

During the Democratic Convention, I watched the absurdly short speeches allowed to the women senators, representatives, and governors and sadly concluded there was not a Hillary in the bunch. There wasn't a Palin either. Democrats seem to be underestimating her. She is an American original, a women Daniel Boone, and the media as well as progressive bloggers seem obsessed by her.

I want us to campaign against her as we would against any conservative Republican. But along the way, we might want to celebrate the historic nature of a woman with a young child campaigning for major national office.

Hillary's comment seemed right: "We should all be proud of Gov. Sarah Palin's historic nomination, and I congratulate her and Sen. McCain. While their policies would take America in the wrong direction, Gov. Palin will add an important new voice to the debate.”

Please refrain from telling a mother of 5 how to mother. It is already obvious that his father and his sibs are very good at nurturing Trig. Being in the thick of things is good for babies.

I have always understood Hillary supporters who are still not on board with Obama. It was not about Hillary. It was about the sexism and misogyny of the Democratic Party. It was about the Democratic Party's offering women little more than Roe vs. Wade. I think Hillary's speech convinced many of them, but the sexist onslaught on Palin might reopen the question. I am sadly concluding that if I want to continue to work hard for Obama, I better not read the progressive blogs I couldn't read during the campaign. Every time I read, "what kind of mother.." I want to make one fewer phone call, register one fewer voter.

August 24, 2008

Weekend Visit with All My Daughters

Ripples

"We drop like pebbles into the ponds of each other's souls, and the orbit of our ripples continues to expand, intersecting with countless others. " J. Borysenko

"We drop like pebbles into the ponds of each other's souls, and the orbit of our ripples continues to expand, intersecting with countless others. " J. BorysenkoI once treated a young Irishman struggling with gay identity issues. Introducing him to James Baldwin was my crucial intervention. A friend, a ER psychiatric social worker at a large municipal hospital, has an office filled with books that he gives away. Chris believes many people experiencing the spiritual emergency of acute mental distress need a good listener and the right book, not hospital admission and mind-dulling drugs.

Being a La Leche leader was also a deeply rewarding way to create ripples. In the days before cordless phones, I use to have a phone cord that stretched anywhere downstairs, from the front to the back door, so I could give breastfeeding suggestions and make sure my kids weren't painting themselves purple or making potions to feed to the baby or decorating the playroom with talcum power and desitin.

Blogging, commenting, and linking allow us to throw even more pebbles.

August 22, 2008

Duck and Cover, McCarthy, Assassinations, Vietnam

This is a picture of Robert Kennedy speaking at my graduation from Fordham University in 1967. RFK was running for president in 1968 when he was assassinated June 5, ten days before my wedding. I had a final wedding dress fitting the day of the assassination, and I was in tears the whole time.

This is a picture of Robert Kennedy speaking at my graduation from Fordham University in 1967. RFK was running for president in 1968 when he was assassinated June 5, ten days before my wedding. I had a final wedding dress fitting the day of the assassination, and I was in tears the whole time.My first specific political memory centered around the duck-and -cover, hide-under-our-desks, exercises that were a regular feature of my early school life from age 5 on. I knew enough about nuclear war to be terrified. We lived one mile away from an air force base, and I used to go out to the backyard, look up at the planes, and try to determine if they were American or Russian. I remember getting a book out of the library on aircraft identification. When I heard Joseph Stalin died, I remember asking if that meant no one would drop atom bombs on us.

In 1954 I had a severe case of the measles and Grandma Nolan came to help nurse me. She was listening to the Joseph McCarthy army hearings. Hatred of McCarthy's voice might have shaped my entire political development. In 1956, just turning eleven, I fell madly in love with Jack Kennedy as he made an unsuccessful bid for the vice presidential nomination. A good catholic school girl, I was initially attracted by his Catholicism; ten minutes later I was smitten by his intelligence, wit, and charm. I was luckier than his other women. Loving Jack Kennedy was good for me. I read about politics and history. From 1956 to 1963, I read everything I could about Kennedy, politics, American History.. When I was 15 I did volunteer work for his presidential campaign.

In high school we had political debates to imitate the famous Kennedy/Nixon debates and I represented Kennedy. What he believed in, I believed in. Gradually I moved to the left of his pragmatic liberalism. Certainly Kennedy was responsible for my decision to major in political science in college. Kennedy's assassination, occurring in the fall of my freshman year in college, devastated me. I felt like there had been a death in my immediate family. I quickly transferred my political allegiance to Bobby Kennedy.

I cannot precisely date my interest in and commitment to civil rights. When I was a freshman, I joined my college's Interracial Understanding Group. I was envious of those college students who could afford to spend the summer down south registering voters and didn't have to worry about money to pay their tuition.

Gradually during college I became a pacifist. Opposition to the Vietnam War right from the beginning was the catalyst. My husband to be, John, applied for conscientious objector status and was willing to face jail rather than be inducted. We became very active in the Catholic Peace Fellowship, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, and the War Resister's League, all pacifist organizations. We went on several anti-war demonstrations both in New York and Washington. I briefly attended Stanford University where resistance to the war was at its height. Almost every afternoon, David Harris, Joan Baez's future husband, spoke out eloquently against the war.

My first job after Stanford was as an assistant to Victor Riesel, a labor columnist, who had been blinded by acid thrown in his face by the mob who controlled the waterfront he was exposing. My assignments included reading the AP ticker to him every day, clipping and reading articles in about 20 newspaper and labor papers. This was in 1968, when King and Kennedy were assassinated, when anti-war protect was at its height, so thinking about politics was my job.

After I returned from Stanford, I had rented a room from an elderly women on the Upper West Side, who supported herself by taking in borders. I spent most of my time with my fiance and didn't want my parents to know it. (I now know they saw through me.) I wasn't supposed to use her phone. I had gone to bed very late; I had stayed up to hear the results of the California primary. I was ecstatic; Bobby had won. I always woke up to a clock radio. As I groggily came to consciousness the next morning, it took minutes to penetrate what they were saying. At first I told myself they were talking about someone else. I crept into the hall and used the telephone for the first time to call John. I was crying so hysterically he thought something had happened to my parents or brothers.

I was working for Victor Riesel, the blind labor columnist. He had been blinded by racketeers because of his investigations of waterfront corruption. Acid had been thrown into his eyes. He was too proud to learn Braille, so he always hired bright young political women to be his eyes. My job was to read about 7 newspapers and 40 labor newspapers and bring to his attention anything that might provide column ideas. The equivalent of the internet was a constantly running ticker tape. All day and all wee I had to read him about the assassination between my tears. This was less than two months after MLK had been shot. The world was shattering, and it was my job to read about it and talk about it all day, everyday.

My husband escaped jailed by getting a high number in the 1969 Draft Lottery. I will never forget the night. I arrived home from work when they had reached 50. As time when on and they didn't call out John's birthday, I was convinced he had been in the first five. His number was 339. For the first time in two years, we could plan our lives together without worrying about a jail sentence.

Pride Overcomes Anxiety

"My 28-year-old daughter has just accepted a summer internship in Rwanda. Seven years ago, a million people were killed in three months in the worst genocide since the Holocaust. She is getting a master's degree in international affairs at Columbia, specializing in human rights, transitional justice, and Africa. If she wasn't going to Rwanda, she would have gone to the Congo. I am fiercely proud of her. But I worry about how to handle my fears as she goes from one world flash point to the next. I want to support her, not burden her with my anxieties. I would like to share experiences and ideas with other mothers of children whose idealism and dedication take them into danger. "

Learning not to burden my daughters with my anxieties is a lifelong struggle. But my anxiety is not nearly as great as my pride:

The daughter I was so worried about, Vanessa, co-edited this new book, which is being ordered for international relations classes throughout the country.

The daughter I was so worried about, Vanessa, co-edited this new book, which is being ordered for international relations classes throughout the country. Penguins

This picture brings back many memories, whether fond or not I have to puzzle out. From first grade through high school graduation, I was taught by the Dominican Sisters of Amityville, Long Island.

This picture brings back many memories, whether fond or not I have to puzzle out. From first grade through high school graduation, I was taught by the Dominican Sisters of Amityville, Long Island.

My new post-World War II community did not yet have a Catholic school. My mother carpooled, so I could go to Holy Redeemer in Freeport for first and second grade morning classes. With so many Catholics eager to send their kids to Catholic schools, they offered split sessions. Then I took a bus to the closer Queen of the Most Holy Rosary in Roosevelt for third through eighth grade. I was in the Queen's first graduating class.

My first grade teacher taught two classes of 60 children, one in the morning, one in the afternoon. All of us learned how to read and write, both printing and cursive. She recognized better students and gave them additional challenges. I craved gold stars on both my papers and my forehead. Regularly, I was sent to the second grade teacher, Sister Paula Anne, to report my latest accomplishment. I was her teacher's pet before I started second grade.

The tall nun on the right is Sister Miriam Francis; she was the principal at both Holy Redeember and the Queen. She died3 years ago at age 93, having worked well into her 80's. I wasn't surprised; in retrospect she was an amazing educator. A tall, elegant, brilliant woman, she effortlessly ruled her 800 students with a clicker; she never had to raise her voice. One click, and we were instantly silent and attentive. She knew the name and the history of every student in the school. We all respected and admired her, were willing to work hard for her praise.

I was a very good girl. In seventh grade Sister Miriam Francis told me I could not have had a more perfect record. So I was never the victim of a nun's wrath, never had an eraser hurled at me, never was hit by a pointer, never had to stay after school to clean the blackboards, never was ordered to put my gum on my nose, never was compelled to bring my embarrassing private note up to the front, so Sister could read it to the entire class. Destructively, my innate shyness was reinforced, however. Good students only answered questions; they never asked them. Class discussion only occurred in high school history and English courses.

Most of the nuns were very young. Many had not yet been to college but were expected to teach classes of over sixty students. My young, beautiful physics teacher, who used to flirt with the boys, was one chapter ahead of us in the regents review book. None of my classes were chaotic; I simply can't remember how they did it. The nun's habit must have disguised a superman costume. I loved grade school, but was critical of high school. I resolved never to send my daughters to strict Catholic school that prized obedience over creativity.

As the negative memories fade, I can appreciate the excellence and rigor of my education. Writing this post has been a revelation. I have never publicly appreciated the penguins. For 8 years I edited books on the basis of my grade school English grammar classes. I always enjoyed diagramming thousands of sentences, especially at the blackboard. We had fantastic geography lessons. Every classroom had many world maps, rolled up in front of the blackboard. I loved drawing maps. A test would be a continent map with the outline of each country. We had to fill in the names. We were given a US map outline and had to fill in the state and its capital. We would never have been allowed to graduate from eighth grade if we could not fully explain Social Security.

The nuns were the only professional women I knew. As a group they were amazingly hard working and dedicated; most of them were warm, kind women. I remember only one mean nun in high school, Sister Jean Paul, who taught eighth grade, the nun on the left of the picture. She loathed FDR and made no pretense of being objective. The class wore black armbands the anniversary of his death and sniffed audibly whenever Sister mentioned his name. Too pull off such a massive group effort, we had to have learned lots of American history.

The high school curriculum was rigorous--4 years of English, Social Studies, Math, Science (Earth Science, Physics, Biology, Chemistry), Religion, Art, Music, Gym, and Two Languages, including Latin. As freshman, we had a half year library science course, mastering the card catalogue and the Reader's Guide to Periodical Literature.

In English class, we loved reading aloud all of Shakespeare's major plays. We were expected to memorize the major soliloquies and sonnets as well as many English and American poems. We read Dickens, Austen, Elliot, Conrad, Dostoevsky, Hardy, Shaw, Ibsen, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Steinbeck.

Sister Grace Florian was the best teacher I ever had in my 20 years of education. She taught first year Latin and senior year English literature. She was brilliant, funny, and demanding. I still have the Jane Austen paper I wrote for her. It is rather good, but Sister Grace Florian incisively criticized the content, the typing, the organization, the grammar, the footnotes, the bibliography. Sister Mary Cyrilla, who taught senior religion, was a fervent believer in Vatican II. Questioning traditional Catholic beliefs were encouraged. She later spent 15 years teaching at the seminary, where men study to be priests. Sister Mary Luke was an excellent French teacher; Sister Gloria Marie taught me to love Math so much that I considered it as my college major.

My friends and I ran the high school newspaper, the Agnesian Rock, and were members of the Speech and Debate Clulb. Debate was enormously challenging, requiring countless hours of library research. We had to argue both sides of each years's resolution, always a major political policy controversy.

But all was not ideal. Science was very weak. There were no female sports, because the champion boys basketball team needed the gym all year round. We had no choice but to apply to Catholic colleges. Those who wanted to attend non-Catholic colleges were refused recommendations. We were regularly taken to Church service; we had to go to confession once a month. In grade school, we had to report our attendance at Mass every Sunday; missing Mass compromised your religion grade.

My mother was an active member of the Women's Ordination Conference. I occasionally attended meetings with her, even though I had not been a committed Catholic after age 18. Many of its members were older nuns; everyone seemed to have a Ph.D. There are very few young women entering the convent. Catholic school kids aren't taught by penguins anymore.

Anne the Bold

From my journals, 1974-1975

From the time Anne was 10 months old, I took her twice a day to Central Park, particularly one very large playground. Anne would casually wander off almost 100 yards away. As long as I was within eye range and met her eyes and waved when she glanced at me, she seemed perfectly confident. One nightmarish day, she managed to slip out between the playground bars and head for Central Park West. I didn't know I could run so fast.

At 15 months Anne would go down slides and climb up jungle gyms that three year olds would avoid. By 2 she was so physically competent that I felt confident about sitting on a bench and watching from a distance as she clambered over a climbing structure designed for children 6 and up. She hardly ever cried if she fell down or bumped into something. Anne was happiest learning new physical feats. She loved the water; at one she would fearlessly walk into the ocean and laugh if she were knocked down. She was physically fearless yet not particularly reckless except about things she could not possibly know about. She was always ahead of other kids in trying something new physically like walking up the slide backward.

Anne in her twenties:

From Niger:

One month ago, I sat in a grass hut in a small village in Niger called Koyetegui, and watched democracy in action, Nigerien style. The five members of the Bureau de Vote sat on overturned pestles normally used for pounding millet, and offered me a seat on a woven mat. And so I sat, as the sun set and the kerosene lantern was lit, and watched as the chickens were chased out of the hut and the entire village crowded into this cramped space to watch the solemn counting and recounting of the 132 votes that had been cast in this tiny district. When the vote counting was over and the report had been filled out and duly sealed with wax, I rode back to the regional capital of Dosso with the ballot box to turn in the election results. It was only the next day that I learned from my driver that the chief of the village had presented me with a gift of an enormous river squash. I spent the entire ride back to Niamey replaying the events of the past few months in my mind, wondering how I had ever gotten to be so lucky.

From applications to graduate schools in International Relations:

In three and a half years, I visited over 75 cities in 53 countries in Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. In several countries–Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Nepal, Benin, Curacao–I was the first AIRINC representative to conduct a survey. I have had the opportunity to do amazing things in my life. I have seen some of the truly wondrous places in the world, from the Sahara desert, to Machu Picchu, to the Mekong River Delta. I have jumped out of a plane in Maine and been seventy feet underwater in the Caribbean. I have witnessed one of the poorest countries on earth usher in a new era of hope and democracy.

My post to a Salon Group, 2001:

My 28-year-old daughter has just accepted a summer internship in Rwanda. Seven years ago, a million people were killed in three months in the worst genocide since the Holocaust. She is getting a master's degree in international affairs at Columbia, specializing in human rights, transitional justice, and Africa. If she wasn't going to Rwanda, she would have gone to the Congo. I am fiercely proud of her. But I worry about how to handle my fears as she goes from one world flash point to the next. I want to support her, not burden her with my anxieties.

You can imagine how happy I am that Anne is working for an international peace organization in Manhattan and mothering her 5-month-old son. She is only 50 minutes away by Long Island Railroad. However, I have not learned my lesson. I gave my grandson the globe beachball.

Favie

This post needs to be read after reading the earlier one on inconsistency. When I forbade Anne to bring her blanket to the playground, I forgot to add, "And you can't bring it to Niger when you are 28 either." This essay was part of Anne's grad school application to Columbia's School of International Affairs, which accepted her. Reading this should bring comfort to all of you who are learning how clueless I was in the early years as Anne's mother. Our children are far easier on us than we are on ourselves.

You are to be photographed with one of your personal belongings. What is the object and why did you select it? Three days after I was born, my father’s mother presented my nervous new parents with a gift: a baby blanket. Loosely woven out of fuzzy white acrylic yarn, interspersed with strands of pale blue, pink, and yellow, and bordered with a satin ribbon, it soon became a permanent fixture in my crib. The earliest black and white photographs taken of me–so early that my newborn legs had not yet uncurled–feature the blanket. There is a photograph, a favorite of my father’s, that shows an infant Anne just learning to hold her head up, sprawled on the blanket with a fledgling copy of Ms. magazine propped over her back.

When I learned to speak, I started calling the blanket “Favey,” a name that baffled my parents until they realized that it was two-year old shorthand for “favorite blanket.” My parents, I now realize, were unusually accepting of security blankets and dependency needs in general. When I was four, there was a famous incident at a dance recital when the teacher refused to let me perform in front of the parents with my blanket. My mother defended me, and I sat out the show. The teacher prophetically warned my mother that I would “make mincemeat” out of her. I prefer to think Anne eroded the old self and help me grow a much more understanding, gentler one. She was not entirely wrong, but I soon learned that there were negotiations in store when I grew older about where it was and was not acceptable to bring Favey: the New York City Ballet was out, but the babysitter’s house was perfectly fine.

I hung on to Favey long after the point that most children give up their security blankets. The blanket suffered its share of wear and tear over the years–the satin border disintegrated, the colored stripes faded, and, most horrifically, my little sister cut a strip out of it to get back at me after a fight–but it stood up remarkably well. It became a standing family joke that I would bring Favey to college. Of course, as I grew older, I developed new and revealing uses for my blanket: I started sleeping with it over my eyes in order to block out the light that I was too lazy to turn off when I had fallen asleep reading in bed; in junior high, I tied it around my wet hair when I went to sleep so that it would be manageable in the morning.

I outgrew these uses for the blanket, but I never seemed to outgrow the blanket itself. When I started college, Favey came with me. I didn’t always sleep with it, but it was always there. It became the only superstition of my life: getting rid of it seemed equivalent to changing your routine when you’re on a batting streak. When I finished college and started traveling around the world as a cost of living surveyor, I brought it with me for good luck, even if I didn’t always remember to unpack it from the suitcase. One of my favorite moments of surveying came when I returned to my hotel room in Hong Kong after a long day only to find that the hotel maid had artfully draped my tattered blanket across the pillow with a mint. When I packed my bags to spend the year in Niger, the blanket came with me. At some point it will need to be retired before it disintegrates completely. I would like to preserve it and hand it down to my own daughter some day.

I have had the opportunity to do amazing things in my life. I have seen some of the truly wondrous places in the world, from the Sahara desert, to Machu Picchu, to the Mekong River Delta. I have jumped out of a plane in Maine and been seventy feet underwater in the Caribbean. I have witnessed one of the poorest countries on earth usher in a new era of hope and democracy. I hope to have a long life in which to add to this list of memories and accomplishments. But ultimately, I believe it is the quality of the love we have shared with others by which our lives should be measured. I can think of no better witnesses to my life than my family–mother, father, three sisters, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins too numerous to count

I love and admire my family for more reasons than I could possibly enumerate on this page. They have always been the most important part of my life: the context in which I first began to define myself as well as my safe haven. That one shredded bundle of acrylic yarn, more gray now than white, is a repository for my memories and a reminder of where I came from. My parents, who respected and trusted a child enough to let her hold on to a security blanket long after others thought she had outgrown it, gave me a valuable gift. I learned from an early age that my own judgment could be trusted, and the confidence that this trust brings has granted me the freedom to strike off in directions that others fear.

Favey at the moment rests at my house. Apparently, now that she is a mother, Anne doesn't need favey. Perhaps she thinks it is a better favey for a daughter. Amusingly, my grandson seems to be getting attached to a burp rag, and everyone is trying very hard to convince Michael to get attached to an adorable light green textured bacon and eggs blanket. My family is taking the question very seriously. Michelle argues that a hotel maid in Hong Kong might be appalled by a 27-year-old burp cloth and Michael will be deprived of his mint.

August 20, 2008

DSM Game

included. I remember when we were studying the DSM in Social Work school.

I was one of the few people who didn't think at least 25 diagnoses applied

to them since I already knew I was bipolar.

I recommend a book by Dr. Paula Kaplan called, 'They Say You're Crazy."

Remember up until the gay rights movement, every gay individual in the US

had a DSM classification.

I propose a new game show, DSM-IVR where you get to assign

numbers to every famous person in history, every literary character, every

character in the Bible. DSM and the Bible is the best game of all. No

flaming in this sacred time; I am a deeply religious person. I am using

the Bible to ridicule the DSM -IVR.

It would be a great family game as well. All you have to do is purchase

enough copies of the pocket edition, and you and your friends will have a

surefire entertainment for life.

Psychiatry and Literature

Rarely explored is the role that a common literary experience plays in therapy. If a client refers to particular books, poems, songs, I would try to track them down. If I didn't have time to read them, I at least skim them long enough to understand the basic themes or characters.

I always pay careful attention to the books my clients carry into the session. That is my first question. "What are you reading? Can I see the book? I gget my best book recommendations from my clients." I love it when clients ask me my favorite novel. During my initial intake, I ask them if they have a favorite novel. I often ask them what they are reading if I know they are readers.

I had two clients who were reading the same novels as I was. I am comfortable revealing the coincidence since I think it indicates a strong therapeutic alliance. If a client brings up a movie she has seen this weekend and I saw it too, I would certainly reveal that. Some rather strict Freudians would rather spend the session analyzing why the client needs to know what you are reading and seeing, rather than answer a simple question.

In my experience, just as clients of Freudians have Freudian dreams, clients of Jungians have Jungian dreams,clients of therapist/ librarians spontaneously talk about books.

In my 20's I was a supervisory editor for Basic Books, the American publisher of Freud and many other psychiatry books. The psychiatrists I encountered were mostly refugees from the Nazi's. They were immensely cultured, learned men, deeply committed to music, literature, and art. Too many psychiatrists today are narrowly educated pill pushers who are ignorant of the classics of world literature. Patients could go to a psych ER, give the name of their favorite literary character, recite the plot of the book as their symptoms and be admitted as a paranoid schizophrenic. Maybe this could be a successful reality show for English majors.

I have gone to psychiatric conventions and introduced myself as Dr. Jane Austen. It pains me how few shrinks get the joke. In my generation, not knowing Jane Austen meant you hadn't graduated from high school. All the drug reps get the joke however, and are delighted at more evidence of shrink's ignorance.

Discovering Childhood Bipolar Disorder

I want to investigate many insufficiently researched questions. Are other countries undergoing the same childhood bipolar epidemic or is this an American phenomena? When and how was the supposed of epidemic of childhood bipolar disorder suddenly discovered? How many of the early pioneers were funded by drug companies? Have any longitudinal studies been done, comparing the life trajectory of kids diagnosed and medicated and kids whose parents refuse medication?

Has the breakdown of the extended family and small families increased the number of kids in serious trouble? Why is there such a striking absence of social criticism about the so-called epidemic of bipolar children? For the last 30 years American society has conducted an unprecedented experiment in having young children cared for by a rapid turnover of strangers--not parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles. Babies as young as two months spend their day in group care, with its inevitable lack of respect for children's individual temperament and biological rhythms. Both mother and father work long exhausting hours without the support of nearby grandparents, aunts, uncles. Schools are obsessed with testing, neglecting the art, music, writing, play that nurture a child's creativity.

Since I was 40, I have struggled with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder for 20 years. I have personally ingested the medications now being inflicted on young kids. Even my strong intellect and excellent education could not prevail against the onslaught of depakote or risperdal. My IQ seemed to drop thirty points; I lost my lifelong writing ability as well as any motivation to write.

How many psychiatrist prescribing drugs for young children have taken them?American society has come to regard children as high-end luxury items parents insist on purchasing and then whine that society should take some responsibility. We have the least child friendly society in any Western country. Do we need more social change and fewer psychiatric drugs?

August 11, 2008

Toward Evening

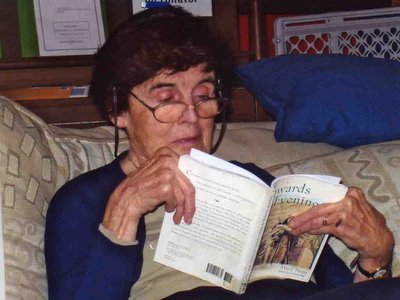

This is one of my favorite pictures of my Mom, taken in late 2002, about 18 months before she died. She is reading Towards Evening: Reflections on Aging, Illness, and the Soul's Union With God; rather incredibly, the author is Mary Hope. Here is the publisher description: "Constantly rushed by the urgent demands of home and workplace, we often long for a season of solitude--an uninterrupted time to rest, meditate, and pray. Author Mary Hope found this time in late middle age, when she began this journal as a 'memorandum in preparation for . . . the perfect union with God.' Her entries never minimize the pain, loneliness, and fear that accompany aging, yet her vision soars beyond life's trials to God's blessings in changed circumstances."

This is one of my favorite pictures of my Mom, taken in late 2002, about 18 months before she died. She is reading Towards Evening: Reflections on Aging, Illness, and the Soul's Union With God; rather incredibly, the author is Mary Hope. Here is the publisher description: "Constantly rushed by the urgent demands of home and workplace, we often long for a season of solitude--an uninterrupted time to rest, meditate, and pray. Author Mary Hope found this time in late middle age, when she began this journal as a 'memorandum in preparation for . . . the perfect union with God.' Her entries never minimize the pain, loneliness, and fear that accompany aging, yet her vision soars beyond life's trials to God's blessings in changed circumstances."Mom coped with adversity by prayer and by reading and learning. In this picture, she is doing both. She probably read more books than anyone I have ever known. When I was working full-time in the library, she came over almost every afternoon to stay with my daughters Rose and Carolyn. Every week she seemed to read every book I had taken out of the library. Only our love of our family brought us closer together than our love of reading.

When her casket was open during the wake, I place in her hands a copy of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice that she had given her bored 12 year old daughter one hot summer afternoon. My love affair with Jane Austen has endured my entire life. As a history teacher, Mom shared wonderful books with the whole family. We both read unfailingly read what the other recommended. I can't say that of anyone else in my life. Our similarly furnished minds helped us overcome are very dissimilar temperaments.

--

Posted By Matriarch to Matriarch at 8/11/2008 01:19:00 PM

August 10, 2008

She Looked on Tempests and Was Never Shaken

Tomorrow is my mother's birthday. She would have been 87. She died April 9, 2004. My daughter Rose, a human rights lawyer and a writer, paid tribute to my mom the week she died.

"I knew her as my Grandma, and I knew her best when I was a kid or a teenager, and that seems to be the only way I can write about her. So. Here is the best composite sketch I can come up with:

She enters the room, and calls out “greetings, greetings.” (Or, if it’s our house in Baldwin, she shakes her head, says “chaos, chaos,” and promptly misplaces her purse.)

She is always, always moving—that’s the first thing you have to know about her. This occasionally verges on the absurd--she used to do laps around McDonald’s by the side of the highway on long trips, and I remember Aunt Sherry once whispering to me “right, no more coffee for you”, as Grandma completed her fourth circuit of the kitchen and stairs on a rainy day in New Woodstock. And when she breaks more bones in the course of a year than the typical casualty rate of a Koch ski trip, or you’re trying to pack up your college doom room, it’s downright unnerving.

But for the most part it’s a very good thing. I don’t know how many countries she went to, or how many lobbying trips to Washington D.C., but I remember our trip to France together; and her descriptions of how Ted Kennedy’s new wife seemed to be doing him good, and which Congressmen were decent guys in spite of being Republicans. And I’ve more than lost count of the times she took my sisters and me to the pool, or the beach, or to visit one of our relatives. But I’ll never forget that the way back from Brian and Maura’s house requires pulling into the Croton Library parking lot and doing a U turn. (At this point, of course, it’s partly because Uncle Brian refuses to tell us the alternate route.)

She also took us into New York City a lot, but the trip to Manhattan I remember the best was the least successful. I was in eighth or ninth grade, and Carolyn was in fourth or fifth. Grandma took the two of us and my sister’s best friend into New York for Carolyn’s birthday. We were going to Central Park and a museum, I think—I’m not sure because we never got there. Grandma’s route to New York was even more circuitous than the way home from Croton. The Long Island Railroad was too expensive, and parking in Manhattan was right out, so she would drive to a municipal parking lot in Queens where you could park all day for $2, and then walk ten minutes or so to the subway—I don’t remember which station, somewhere near the end of the E line. This time, though, our meter was broken. I suggested we move to another space, but she was not willing to waste those quarters, so she wrote a note and taped it to the parking meter. Unfortunately, in the confusion, she left her car keys sitting on the driver’s seat—she realized this somewhere under the streets of Manhattan.

We turned around, and no one had broken the window or stolen the car. But here, I thought, was an object lesson for Grandma—moderation in all things, including frugality. She’d have to pay for a locksmith, which cost much more than the extra quarters or, God forbid, a train ticket.

She did no such thing. Instead she asked a rough looking young man on a nearby sidewalk to help her break into her car. He was happy to assist. When he could not get the door open, he called over a friend. Who said, after a few more unsuccessful attempts to pick the lock, that what they really needed was a crowbar, but since he didn’t have his around and Grandma was not crazy about that, they’d better ask another friend. Who said, and I quote, “what we really need is a Puerto Rican.”

I don’t know whether they found a Puerto Rican, and I don’t remember how long we stood there, Grandma smiling encouragingly and offering occasional advice, or how many neighborhood kids were debating the best way to break into a Toyota Camry by the end—it’s probably somewhat exaggerated in my memory. I can tell you that in the end, the simple yet elegant coat-hanger-through-the-window-to-pull-up-the-button-technique did the trick. The lock suffered some damage from the good Samaritans’ enthusiastic efforts, but you could get the door open more often than not. And from then on, we parked in the driveway of a high school friend of Grandma’s—10 minutes further away from a subway station even further down the E line, but $2.00 cheaper than the municipal lot and much less risk of a break in.

(As I was writing all of that, I realized---it’s not quite accurate to say she was always moving. I just remembered the nights in Henry Street when she would tuck us in, and tell us to lie still and imagine we were floating on a cloud. There were also her “yoga,” excuse me, ‘yoger” exercises. But if I ever want to finish this, I should move on, so….)

She was incredibly smart, and incredibly interested in the world around her—whether it was the history of the China lobby or when any of her nieces, nephews and grandchildren would finally, in her words “find yourself a mate.”

She also had the strongest faith of anyone I’ve ever known. Maybe it was that combination, that fierce intellect and that certain belief and trust in God, that made her so strong. Much more often than not her beliefs coincided with the Catholic Church, but when they differed she was not shy about saying so…On most of the many nights I slept over at the house on Henry Street, I wore a polyester blend, 1970s issue T-shirt that said in glittery bubble letters “When God Created Man, She Was Only Joking.” And I remember her telling me about sneaking in inclusive language to her frequent readings at St. Martha’s, much to the new parish priest’s chagrin.

And on the much more frequent occasions when her children and grandchildren did something she disapproved of—she let us know in no uncertain terms, but there was never a single moment’s doubt that she loved and accepted us anyway. I’ll always think of her when I read these lines from Shakespeare’s 116th sonnet::

Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O no! it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken.

I know, it’s a love poem—and a truly bizarre choice for a description of one’s grandmother. But—getting back to photographs, and with apologies for the embarrassment this may cause certain unnamed relatives of mine--I defy you to find a better or funnier illustration of Shakespeare’s words than these pictures of Grandma Mary, Grandpa Joe, and their wayward offspring in 1974.

Growing Up With 5 Younger Brothers

My dad was an actuary; my mom was a housewife who became a history teacher and activist after I left home. I have 5 brothers, 18 months, 3 years, 7 years, 11 years, and 13 years younger. All married relatively young; one brother divorced and remarried. They have 6, 0, 2, 1, and 2 children respectively. There is a lawyer, a chemistry professor, a teacher, a nurse, and an accountant. They live in Maine, upstate NY, North Carolina, Westchester NY, and Long Island NY.

Taking care of my toddler grandson Michael three days a week, I have recaptured many memories of my brothers as small boys. Growing up, I was extremely close to my brothers; we spent most of our free time together. We loved the beach, ice skating, roller skating, tree climbing, summer vacations, backyard baseball, touch football, and badminton. We played endless ping pong and knock hockey games, card games, Monopoly, and Scrabble. We had the biggest backyard on the block, and our house was always the neighborhood hangout. We had a basketball hoop attached to the garage that was in use day and night. There were no girls on the block, so I always played with the guys. I was passionately interested in baseball, and my brothers used to challenge their friends to ask me a baseball question I couldn't answer.

Looking back, the siblings might have relied on each other too much. Joe, Andrew, and I were not very social; each of us had one best friend and two good ones. We never hung out with a group of peers. We always had each other to play with, argue with, compete with. We always defended our siblings against our parents and against neighborhood bullies. Except for Bob (the 4th child), we never dated in high school.

Rationality, intellect, and academic achievement were the family values, and we all honored them. Competitiveness was subtly encouraged even though my mother would occasionally inveigh against it half-heartedly. Sarcasm and teasing were prevalent; the victim was expected to take the joke. Excessive emotion was scorned; I cried alone in my room. I still find it absolutely humiliating to cry in public and feel critical of women who do. Except for my parents' deaths, I have virtually no members of my brother's crying past 3 or 4. The possibility of my dad's crying was unimaginable. My mother, who had 5 brothers too, always choked back her tears.

We ere encouraged to rejoice in how different we were from most people in our working-class suburban town. We were the intellectuals. When working summers as mail carriers, Joe and Andrew reported that no other families seem to subscribe to the same magazines me read. My dad strongly encouraged us to think for ourselves and not care what other people (except each other) thought. He pointed that the most people were too preoccupied with their own problems to think much about you. My brothers might not be much use for discussing emotional issues, but for intellectually stimulating, challenging conversations, they are terrific.

My brothers can see each other for the first time in 6 months and spend the evening discussing politics, not their personal lives. My brothers insist that they don't have to talk to their siblings frequently to stay close. Each is certain he would come through in a crisis, and their track record is good. We all seem very interested in what the others are doing, but as long as my mom was alive, my brothers would ask my mom instead of calling their brothers. Now I have moved in that family switchboard role.

We still influence each other tremendously. We very much want our siblings' approval. Andrew, the chemistry professor, has been very opinionated about the college and career choices of his nieces and nephews. I have been amused and touched by how each of my brothers checked out my daughters' prospective husbands. We freely borrow each other's expertise. I was worried that the family would scatter after my mom died, but we all have attended the second generation's numerous weddings and sibling milestone birthday parties.

There is now a younger generation; three of us are thriving as grandparents. My parents would have 3 great grandchildren, with 3 more on the way. Everyone adores the babies and showers them with attention and love.

We have always had a strong family identity--intelligent, independent, well-educated, critical, autonomous. Marrying a gorgeous bimbo was not an option for my brothers. When we get together, we all have a good time. We have the same sense of humor, vote for the same candidates, enjoy the same movies. We all take pride in the academic and career success of the second generation. I am aware to what extent this pride in intellectual achievement is a defense against social insecurity and sets us apart from other people. Thankfully, our children have not inherited that limitation.

Having 5 younger brothers has probably shaped me more than any other single influence. I like and sometimes actually understand men and invariably defend them to women. I loathe men-bashing. Until I became a mother, I was far more comfortable in a group of men than a group of women. I enjoyed being the only girl in my political science classes at Fordham, while I was miserable in a girls' Catholic college in freshman year.

I did not consciously want sons. I always told people my 4 girls were my reward for 5 brothers. I always wanted a sister and am sometimes envious of my daughters' closeness. But I love taking care of a grandson and talking to little boys in the playground.

August 8, 2008

Dark Side and My Daughter

Jane Mayer, the New Yorker writer, thanks my daughter, a writer, researcher, and human rights lawyer, for her work on Mayer's new book, The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned into a War on American Ideals:

Jane Mayer, the New Yorker writer, thanks my daughter, a writer, researcher, and human rights lawyer, for her work on Mayer's new book, The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned into a War on American Ideals:"I am also deeply indebted to ********, a meticulous lawyer and scholar, whose sharp eye and encyclopedic knowledge of the legal practices of the Bush Administration's war on terror improved the manuscript immeasurably."

I just got the book. It got a glowing review on the front page of Sunday's New York Times Book Review and is now the fourth best selling nonfiction book in the US.

Struggling Not to Be a Judgmental Grandma

My grandma was only 47 when I was born; my mom was 51 when she became a grandma. I was turning 62 when Michael was born. My girls justly accuse me of being a hypocrite. They went beyond my wildest dreams for their education and careers. Yet occasionally over the last 6 or 7 years, I would plaintively remark how many children grandma had when she was my age. She had 9 by the time she was 62; when she died at age 82, she had 15. I grieve that my mom didn't live to see her great-grandchildren. She would have adored Michael, an incredibly friendly, fearless toddler much like her and his mother.

Perhaps unconsciously I am blaming mom, who shortened her life by her refusal to accommodate to her physical disabilities. She was never the same after she feel down the stairs on her head, stairs she was forbidden to climb without help. Grandma Nolan, who had 7 children and lived to 86, had 23 great grandchildren when she died. Sadly, I realize I probably will not live long enough to meet my great grandchildren. The infrequently discussed bad effect of having children when you are older is that they don't have young or healthy grandparents. I was 50 , the mother of 4, when my grandma died; Carolyn, my youngest (born when I was 37). was only 21 when her grandma died. Michael's dad's parents both died a few years ago.

I was fortunate enough to be able to stay home full-time when my 4 daughters were young. I had originally planned to go back to my editing career, but I fell madly in love with mothering. We had the option of living on one income, which few couples have now. Supporting their career and child care plans is a struggle for me. I take care of toddler Michael 3 days a week while Anne works. She recently decided to return to work four full days and to possibly explore two days a week of day care. Although I could not commit myself to 4 days, I need time for my granddaughters, and I understand Manhattan day care requires a two-day commitment, I interpreted her decision as a criticism of me. We had a difficult few days before we learned to listen to one another. My second daughter Michelle plans to go back to work full-time after a 12-to-14-week maternity leave. She hasn't decided between day care or a nanny. The third daughter Rose has very flexible work options; she is a human rights lawyer whose writing and research skills are essential to her firm. Even though I bite my tongue and question my motives constantly, all three accuse me of being judgmental. I admit I expected at least one of them to stay home the first year at least.

I worry that I will be perceived as favoring Michael, whom I see so much more often. We plan to visit Boston several times a month, but that won't be close to the several times a week I spend with him. I plan to spend two weeks each with Michelle and Rose after the girls were born, but I spent almost three months visiting Vanessa and Michael nearly every day last summer. I need a new external hard drive if I take as many pictures of the girls as of Michael. I have had great fun with a private family Michael blog. I have already announced I am turning that blog over to his parents and will have one daily grandkid blog.

Anne didn't want me there when she was in labor; she and her husband wanted to do it themselves. She wound up with a C-section that she now thinks was unnecessary and wants me to be there next time. When Anne was born, I didn't want my mom to take off from work because my husband and I wanted our privacy. For the other 3, I planned my pregnancies around my mom's schedule. I didn't realize how much I would need my mom after I gave birth. So I should understand why my daughters would react similarly. My being lucky enough to have 4 drug-free births, including two at home, might make my childbirth support threatening. If I had it so easy, what do I know? . My years as a childbirth educator and breastfeeding counselor also contribute to my being perceived as a judgmental

know-it-all.

Being the babysitter who makes it possible for her to work as well as Anne's mother is potentially a quagmire. Anne and I have navigated the challenges reasonably well, considering she is the daughter with whom I have the most turbulent relationship. Anne is very different from me, far more like my mom, who wasn't a worrier. Sometimes I worry that she doesn't worry enough, and then berate myself for judging my daughter.

My mom died 4 years ago. About five times a day I wish I could call her up for grandmothering advice from the one person who knew me and Anne equally well. When I frequently called my mom in tears over my latest struggle with Anne, we used to look forward to watching her struggles with her kids.

I adore my grandson and feel almost no guilt about how I relate to him. I know what I am doing, and I have no other distractions to prevent me from doing it. His parents and I see eye-to-eye on all important parenting decisions. However, I often feel guilt about not knowing how best to support my daughters, how to be genuinely helpful without undermining their confidence in their own decisions. My mom and I struggled with these issues all our lives, so I don't expect any easy answers.

Even writing about this feel fraught with peril. I don't know if my daughters are reading Matriarch or not. Even though I blog under a pseudonym and change all their names, I constantly worry that they will be furious at me for violating their privacy. It is far less problematic to write about them as kids than to discuss our adult relationships.

Thank you again Veronica for inspiring me to write about something I constantly agonize about. Perhaps it will help clarify my thoughts.

--

Posted By Matriarch to Matriarch at 8/08/2008 04:24:00 AM

August 6, 2008

Confused Feminist in Love

Chris, a year behind me in college, planned to be a physics professor. (I was desperate to hide from my family that John was 9 months younger.) When I applied to grad schools, I looked for places equally strong in both physics and political science, figuring a year's separation would make us surer about marriage. If I had known myself better, I would have applied to grad schools in New York City. I went to Stanford University in California, 3000 miles away from my love. I hated grad school, was miserable without John, and left after two months. My parents were puzzled that I had given up an all-expenses paid PhD; I foolishly avoided my family for two months.

I returned to NY, got married , and slowly worked my way up in New York City book publishing. I was never wildly enthusiastic about editing social science and psychiatry books. It resembled grad school, abstract, intellectual, remote from people. In 1971 I attended Columbia Law School, hating it even more than grad school. Why I went to law school was murky. The preceding spring at Richard's wedding, my brother Stephen said, "Mom thinks you should go to law school and make something of yourself." In a retirement interview, my mom told the editor of the high school paper that she would have gone to law school if she had had the opportunities open to women now.

Not Just a Mother

When I was a child, most of the older working women I knew were Roman Catholic nuns. My mother, my friends' mothers, and my aunts stayed home and raised their children. Although I knew I wanted a career, I never could decide what career. I invariably said "I don't know" when people asked me what I wanted to do. But I always added, "I don't want to be just a mother." I valued intellectual acheivement at the expense of the maternal, emotional, intuitive side of my nature. I was sure I didn't want to be just a teacher, a nurse, or a social worker either; the traditionally feminine fields were not for me. I would aim higher.

I was a shy girl who refused to wear the glasses I desperately needed outside the classroom. If any boy noticed me, I must have come across as a dreadful snob since I couldn't see him. I fervently believed that a girl could be smart or she could date. I was as confident in my intellectual abilities as I was dreadfully insecure about my popularity and attractiveness. One of my uncles kept the letters I wrote him when I was in graduate school. They are so embarrassing. Basically I listed the books I had read and the marks I had gotten, comparing them to the marks of my brothers and my friends.

August 5, 2008

I Did Not Set Out to Be a Mother of Four

In one of your posts you stated "I did not set out to be a mother of four." Prior to becoming pregnant with your first child, how did you envision your life unfolding?

First, remember how old I am. I was a college freshman when Betty Friedan's The Feminist Mystique was published. I came of age at the birth of the second feminist movement. From age 12 until I met my first husband when I was 2o, I didn't plan to be a wife or a mother. I believed women had to chose; guys didn't fall in love with intellectual women. I envisioned a brilliant career, but I was unclear what that career would be. I certainly rejected the traditional female careers--nurse, teacher, librarian, social worker. In college my ambitions were clearer. I wanted to be a college professor of political science. John, my fiance, planned to be a professor of astrophysics. From the beginning, we planned to share childrearing and housework. Having 5 brothers makes a woman a feminist.

John was a year younger than I was, When I was applying to graduate schools, I was not yet sure of our relationship. I didn't mention to my graduate advisor that love might be a complicating factor. So I applied to the best schools that would give me a fellowship. I eventually chose Stanford because John wanted to go to Berkeley. When I left for California in the fall 0f 1967, Peter, Paul, and Mary's song, Leaving on a Jet Plane was popular. I can never hear it without remembering how heartbroken I was to leave John.

I didn't last a semester at Stanford. How I interpret my leaving has varied tremendously over the years. At the time I convinced myself that I hated Stanford. They were trying to make political science scientific while huge anti-Vietnam War protests were occurring right outside the classroom doors. Accepting this interpretation meant I ruled out graduate school as a possible choice. Probably I just could not be 3000 miles away from my fiance; we got engaged over the phone. Still later, I interpreted my leaving as the first sign of my mood disorder. I decided to come back to NY and get a journalism job; I planned to go to Columbia School of Journalism.

I didn't get a journalism job and wound up in book publishing. In my stupidest career move, I rejected a job at the New Yorker because it would involve too much typing. I was intimidated by the writing requirements of the Columbia application and didn't apply. I advanced quickly in publishing, then got stuck as a Supervising Editing. I wanted to work with authors to acquire and develop books. Because I was a good supervising editor, I wasn't being promoted. I felt I was editing the books I left graduate school to avoid writing.

So I decided to go to law school. It was an ill-thought out decision. Whose dreams was I fulfilling? Early in 1971, my brother Andrew commented: "Mom thinks you are wasting yourself in publishing. You should go to law school and make something of yourself." When she retired from teaching, my mom told the interview from the school paper that she would have been a lawyer if she had come of age in the 60s. I had a vague picture of myself as a public defender fighting for the rights of the poor.

August 1, 2008

Feminism and Motherhood, August 1976

8/31/76 Since I started journaling, I had many insights into my difficulty in choosing a career. It's intimately bound up with my family, being the only girl with 5 younger bothers. The roots go back a generation; my mother had 5 younger brothers plus a sister she never had very much to do with. In the jargon of early feminism, we were both "male-identified." As a girl, I was very close to my 5 young uncles.

Everything changed when I started high school and started to get attention for being smart. Early in high school I rejected my mother's world and chose my father's world. But even when my father agreed with me intellectually, he never supported me in my arguments with my mother. Instead he blamed me for getting her upset. After my first daughter Anne was born, my dad told me he preferred wise women to intellectual ones. So I rejected my mother's world, yet I was close to my mother and dependent upon her. No wonder we were constantly fighting. What did my mother symbolize to me? Mindless maternity. A good mind going down the drain with thousands of dishes washed ,thousands of diapers rinsed.

I perceived her as a good mother of young children, but not of troubled adolescents, because she accepted things, did not probe, question, challenge the way things were. She found it easier to put others before self because she did not have a highly developed sense of self. I on the other hand was selfish and immature, putting my own intellectual development above all else. I clearly saw a dichotomy--wife and mother versus intellectual. No woman I had ever personally encountered had combined both. In fact, the nuns were the only career women I knew. All my aunts, mothers of my friends, the neighbors were housewives. I was in the process of rejecting Catholicism, so I never got close to any nun for her to serve as a role model. I began to suspect I never would get married, that the only way to attract a man was to play dumb, something I would never consider. I wasn't really rejecting motherhood; I never thought much about it. But when my first boyfriend wanted to tease me, all he had to say was that I was like my mother. I couldn't imagine anything more insulting.

I always sought out situations where I could be the only woman in a group of men. I didn't want to seduce them; I wanted to excel them. I made the mistake of going to a Catholic women's college my freshman year, Nazareth College of Rochester, because they offered the most scholarship money. Almost immediately I wanted to transfer. I told my parents I wanted to switch my major from English to Political Science,, and Nazareth had no such department. I was only interested in college debate after the assistant dean explained that Nazareth had no debate club because "there's something in the nature of a woman that makes it objectionable for her to compete so openly with men."

At Fordham I was usually the only girl in my political science classes. At Stanford, there was only one other woman among the first year grad students. I was positively crushed when I realized how many women there were at Columbia Law School. It wasn't enough for me to think like a man; I had to think better than a man. I only made friends with women who had also rejected the conventions of femininity.

Everyone in the family perceived my dad as smarter than my mom, particularly her. She would always send us to him for the hard math and science homework. We were amazed when she returned to college and got all A's. Thehe mother who graduated from college in 1967 and grad school in 1968 and taught high school history was a different mother than the one I knew growing up. Looking back, I see my mother's ambivalence. My evident influence over her, that fact that she went to college when her youngest entered school, how hard she worked as a student and a teacher, her still emerging feminism all suggest she might have been giving me contradictory messages.

Unquestionably, she identified with my opportunity to go away to college, my getting a NYC apartment, my opportunity to get a PhD all expenses paid--such chances were unheard of among her friends when she was my age. When I told her I was dropping out of Stanford and marrying John, she attempted to dissuade me. She never attempted to convince me to have a baby before I was ready to have one. Her reluctance to pressure me seemed to indicate that she would have done the same thing if circumstances were different. I was destined to go beyond her wildest dreams, and she would be very happy for me. Throughout my adolescence and young adulthood, the "masculine" intellectual, achieving, ambitious, competitive side of my personalty was nourished and encouraged by everybody.

So many of my school and career problems are unquestionably related to my constant striving to be like my brothers,, to deny my womanhood. That's why I am only discovering child development as a possible career. Any career involving children was feminine and therefore unworthy of my superior intellect. It was against all my principles and preconceptions to feel overwhelmingly maternal toward Anne. I thought the maternal instinct was a myth and suddenly I was wallowing in it. I suddenly understood had my mother could have decided to have six children.

I still cannot understand how I suppressed the woman who can't pass a baby stroller without smiling and flirting with the baby, whose favorite During that first year after Anne's birth, I had to learn that I needed people, not just brilliant intellectuals, ordinary people to talk to, to get ideas from. I needed to relinquish my faith in the overriding importance of rationality and learn to trust my emotions. I could learn from almost every mother I met; I could get support from most mothers I met if I could learn how to ask for it.

However, I should have reread this journal before deciding to become a public librarian and a social worker. Having four daughters has not removed the influence of my five brothers and my five young uncles. I still don't do very well in women-dominated professions. I have always been more comfortable with male psychiatrists, both as a patient and as a therapist. I still love competing with and debating with men. As a social worker, I worked best with clients who were schizophrenics with serious drug problems and often prison records. I suspect I would have done well as a prison social worker. Late at night, I am comfortable in a subway car that is all men. It is still easier to approach a group of men than to approach a group of women. All my life I have struggled with the fear that women won't like me if they really know me. I've never learned tact. Men are easy; they enjoy bright, argumentative women who smile, call them sweetie (because I am not good with names), genuinely admire their ties, shirts, long hair, earings, or beards, and obviously enjoy them.

Proud Mother

Jane Mayer, the New Yorker writer, thanks my daughter for her work on her new book, The Dark Side.

"I am also deeply indebted to Katherine *******, a meticulous lawyer and scholar, whose sharp eye and encyclopedic knowledge of the legal practices of the Bush Administration's war on terror improved the manuscript immeasurably."

July 28, 2008

Confessions of Misogyny

Spending a year in a Catholic girls college in Rochester was the most alienating experience of my life. I was sarcastic, and no one seemed to realize I didn't necessarily mean it. One night my friends and I stayed up all night, discussing politics, sex, religion, life, death, etc. The rumor rapidly spread that we were gossiping about everyone on the floor. Learning from the college dean that "there was something in the nature of a woman that unsuits her for intellectual debate with men" elicited my jail beak to being the only girl in the political science classes at Fordham.

Working in the female-dominated fields of public librarianship and social work was a disaster for me. I never can accept that is the way it is and you can't do anything about it. I am a trouble maker pure and simple. When I am upset, I defend myself by getting more ascerbic and intellectual. I perceive that men enjoy gutsy women who giggle and smile and tease and insult and debate with them lots more than women do. I have always gone to male shrinks.

My most successful social work job was working with a great group of seriously mentally ill guys who were absolutely trapped in the system. Some had been in jail; most had substance abuse problems. I never was so appreciated by a group of people in my whole life. They were so wonderful to hang out with. I excel at eliciting the sanity in crazy people and the craziness in apparently sane people. There are lots of the latter in social work and public librarianship.

I also did extremely well with male gay clients. One told me I must have been a gay male in a previous lifetime I understand him so well. I Another paid me the greatest compliment I got as a shrink: he said I was his only experience of unconditional love. We had a strange therapeutic relationship. Until I treated him, an Irishmen from an utterly abusive family, I never realized how Irish I was.

I have never been hassled on the street by a guy in my entire life. I do smile a lot. I am perfectly comfortable being the only women in a subway car full of men. African American men and immigrants tend to find older, curvier women attractive, which is lovely fun. In the early days of women's lib, women whined incessantly about street hassles. I wondered if I was the ugliest woman in the entire women's liberation movement. I often have long conversations with homeless men. One street person teased me that I looked very friendly ,approachable, happy to talk, sometimes generous depending upon whether I had exceeded my day's handout limit, but I subtly conveyed that I could turn him to stone if he messed with me.

Two days later, I realize that the attacks on Hillary by women both reflect their misogyny and evoke mine. This week, all three female columnists for the NY Times , Maureen Dowd, Gail Collins, and Judith Warner appear to despise women who are not as brilliant, rational, skeptical, and educated as they are. They show little respect for the women who voted for Hillary because of her supposedly manipulative exploitation of gender issues; they seem obnoxiously smug that they understand women's real reasons, not the fantasies the poor little darlings tell themselves . I am not as guilty as they are of despising "regular" women, but I love to hate all highly successful women who, instead of supporting and mentoring younger women, seem to want to push down other women so they will remain in all their glittering exceptionalism on the top.

July 26, 2008

Blocks

Michael is getting the hang of building with blocks. He knows how to put one on top of another. Previously, he loved knocking down buildings we constructed. He also can put bristle blocks together. I would lend him some of our wooden unit blocks, except that he loves to hurl things, and we value our teeth.